What Liberal Arts and Sciences Education Gave Me, and Why We Need More of It

A personal reflection from Leiden University College

When I was eleven, my older sister asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. Instead of giving the expected answers like pilot, doctor, or astronaut, I gave her a ten-minute lecture on why it is pointless to dream about a specific profession as a child, when your only understanding of a job comes from its idealized portrayal on television. She never asked me again.

The problem was that when I did grow up, at seventeen, I felt just as unprepared to answer that question as I had six years earlier. I was struggling to choose a university program. I knew I loved learning and could imagine myself succeeding in many different professions, but I had no idea of which one I was supposed to choose.

At some point, someone told me, “You don’t have to aim to solve world hunger, just pick something you enjoy doing and go with it.” I didn’t know what I enjoyed doing, but I did know that focusing on world hunger sounded like a direction I couldn’t go too wrong with.

So when, when finishing high school (majoring in chemistry, biology and geography and film showing how confused I was) I came across Leiden University College’s Liberal Arts and Sciences (LAS) program focused on “global challenges,” I immediately knew it was what I had been looking for, despite having no real idea at the time what liberal arts or global challenges actually meant.

That program transformed what once felt like a paralyzing lack of direction into a strength. Rather than forcing me to choose a single path too early, it allowed me to turn my curiosity across many subjects into a way of thinking. A way of thinking that embraces complexity and draws on insights from multiple disciplines.

The Pros and Cons of Studying LAS

Put simply, Liberal Arts and Sciences (LAS) education allows you to make one of the most important decisions of your life - your profession - not as a teenager living in their mother’s apartment and worrying about prom, but as a relatively educated 21-year-old who knows who Socrates was and why correlation does not equal causation.

However, all of this comes at a cost. No one understands what you are studying, and they keep asking, making you wish you had just gone to medical school so you wouldn’t have to keep explaining.

In this blog post, I want to answer, once and for all, the question I’ve been asked far too many times over the past three years:

“Filip, what on earth did you study for your bachelor’s degree? Why is there no art involved even though it says so in the name, and why do you love it so much?”

From now on, if you ask me this question, I will kindly send you a link to this post.

So what is Liberal Arts and Sciences education, and why do I think we need a lot more of it if we care about the future of humanity?

What “Liberal Arts and Sciences” Actually Means

The tradition of Liberal Arts and Sciences education dates back to classical antiquity and medieval universities. That long history explains why some of the words in its name no longer mean what a modern reader might expect. Before we dive into the history of the LAS tradition and the 7 reasons why I believe Leiden University College is the best bachelor’s program in the world, let’s make sure we understand what each word in Liberal Arts and Sciences actually means, and why it has nothing to do with being pro-choice or painting.

Liberal: Education for Free Citizens

The word liberal comes from the Latin liber, meaning free. In Roman thought, the artes liberales were the forms of education appropriate for liberi homines, free citizens, not slaves or craftsmen trained for a single task.

The Roman philosopher and statesman Cicero was one of the earliest advocates of this educational ideal. He repeatedly emphasized that education should cultivate judgment and moral responsibility rather than technical skill alone. In De Oratore (55 BCE), he argues that proper education develops the capacity to reason, deliberate, and speak effectively in public life, which are the core competencies of a self-governing citizen. Education, in this sense, was inseparable from civic freedom (Husband, 2013; Nicgorski, 2013).

It is arguably the kind of education one needs to be a valuable participant in what we call a participatory democracy, rather than a convenient tool for populists and radicals on their way to power.

Arts: Ways of Thinking

Arts comes from the Latin ars, meaning skill, craft, or method. This did not refer to art in the way we think of it today, such as painting or music. Instead, it referred to structured ways of using the mind (perhaps similar to today’s buzzword “critical thinking”).

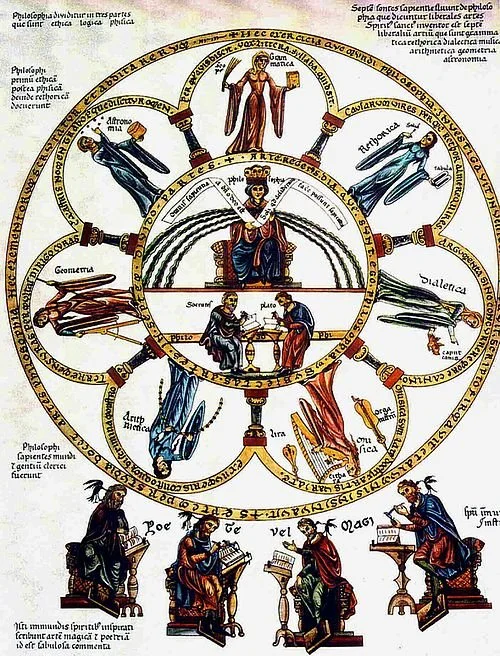

In medieval universities, the arts were formalized as the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, logic), which provided the tools for reading, writing, arguing, and reasoning, and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy), which trained abstract and mathematical thinking (Satchanawakul & Liangruenrom, 2025).

The medieval theologian Hugh of St. Victor wrote in Didascalicon (c. 1120) that the liberal arts are preparatory disciplines, meaning they do not exist for their own sake, but because they train the mind to understand anything else (Sullivan, 2021).

In modern terms, the arts encompass the kinds of thinking we are most concerned about losing in the age of AI: learning new facts, understanding the connections between them, and structuring our thoughts so they can be presented clearly and coherently.

Sciences: Understanding the Why

Science comes from scientia, meaning knowledge and its systematic and reasoned understanding (foundation of the scientific method).

Aristotle in his Posterior Analytics, (4th century BCE) defined epistēmē (scientific knowledge) as knowledge of causes, knowing why something is the case, rather than merely that it is the case. Under this definition, philosophy, mathematics, natural inquiry, and what we now call social science all counted as sciences (Parry, 2003).

How Europe Lost, and Rediscovered, the Liberal Arts

After antiquity, Liberal Arts and Sciences education became institutionalized in medieval European universities. Institutions such as Bologna, Paris, and Oxford were built around the liberal arts as preparatory education. Students first completed a degree in the arts before specializing in law, medicine, or theology.

During the Renaissance, humanist scholars argued that education should not merely transmit doctrine but cultivate judgment, eloquence, and moral reasoning. The goal was to form individuals capable of navigating public life, not only executing tasks.

However, Europe’s industrialization in the 19th century brought a shift toward early specialization and professional training. Education increasingly became about producing “human resources” rather than self-governing citizens. Without claiming any direct causality, I think it is reasonable to suggest that this narrowing of education contributed to the broader social and institutional environment in which political radicalization and mass violence emerged in the 20th century.

During this period, it was ironically the United States where the liberal arts tradition was preserved. American liberal arts universities founded in the 18th and 19th centuries (among them, e.g., Harvard, Princeton, or Yale) emphasized small seminars, close relationships with professors, broad education alongside specialization, and preparation for both professional and private life, instead of a concrete job title (Satchanawakul & Liangruenrom, 2025).

Fortunately for me, and for many other Europeans, Europe began to rediscover this educational model again in the 1990s. Faced with over-specialization and a rapidly changing labor market driven by the internet revolution, several European universities, particularly in the Netherlands, created University Colleges. These institutions combine American-style liberal arts education with European academic rigor (van der Wende, 2007).

One of these colleges is Leiden University College The Hague (LUC), which I was fortunate enough to attend and graduate from.

Leiden University College and the Case for Purpose-Driven Education

LUC is built around the Liberal Arts and Sciences ideal but differs in a few key ways. First, its residential halls and academic spaces are all located within a single building, making the experience unusually immersive in both positive and negative ways. Second, all students follow a program centered on Global Challenges, ensuring every student is a ‘good-doer’ at heart.

After a common foundational year focused on the “arts,” students choose one of six majors: three BA majors which are Culture, History and Society; International Justice; and World Politics, and three BSc majors, namely Earth, Energy and Sustainability; Global Health; and of course, the best one (not by coincidence, the one I chose): Governance, Economics and Development.

Unlike many American liberal arts colleges, where students can study almost anything, LUC’s program is deliberately focused. I believe this element is one of the program’s greatest blessings, as it brings together students who share values and concerns while allowing enough diversity in their core interests and beliefs to facilitate meaningful discussions in classrooms, hallways, and dormitory rooms.

For many of my peers, myself included, LUC remains one of the most formative experiences of our lives, academically, professionally, and personally. I am convinced that this model is exactly what we need in a world shaped by climate change, artificial intelligence, and rising political radicalization.

Here are 7 reasons why:

1) Personal Relationship with Professors

Some of my strongest memories from my bachelor’s degree involve philosophizing with a professor about the tension between Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine on the grass of a park in The Hague; getting eggs thrown at us by teenagers while listening to a professor describe his work on water scarcity in Saudi Arabia on a small boat; or spending ten days at an alternative art festival on a Dutch island discussing anthropology and sustainability with a professor who had lived among the Maasai in Kenya.

One might think these experiences are irrelevant for a career in development finance. But I know they shaped how I approach learning, how I value intellectual honesty, and why I care so deeply about development.

I became convinced that personal relationships with professors are not a luxury, and should instead be a central part of our learning journeys. They are the most effective way to teach someone to seek for the truth even in situations when it is not convenient. Without that, very little of what we learn truly matters.

2) Learning to Think Like a Scientist

Regardless of one’s career path, the ability to evaluate information is essential. I won’t be the first one to point out that in an age of misinformation and disinformation, knowing how to work with primary sources, evaluate assumptions, and understand basic statistical methods is one of the most effective pathways for a functioning society.

Equally important is the ability to communicate findings clearly. Being able to write and speak precisely reduces power imbalances, improves decision-making, and elevates public debate.

LAS education trains these skills through philosophy, statistics, mathematics, and academic writing. This ensures that even if you dropped out after your first year at LUC, you might not have earned the diploma, but you have become a better citizen, and probably a better version of yourself.

3) Interdisciplinary Thinking as a Survival Skill

Most modern breakthroughs do not emerge from a single discipline (few examples are the discoveries of Amartya Sen, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier or Claude Shannon).

Now, imagine small scale liberal arts colleges centered on human health, combining psychology, medicine, pharmacy, and ethics; or LAS focused on technological challenges in the 21st century, merging computer science, AI ethics, and sustainability.

We can no longer pretend that we do not need transdisciplinary conversations like these. Since the end of the Second World War, technological progress has increasingly confronted humanity with existential risks of its own making. If education remains narrowly profession-oriented, we risk producing ever more sophisticated means without clear reflection on their ends. What we need instead is an education system that is purpose-based. We need our universities to train students to take meaningful steps in the right direction, rather than simply the biggest possible steps forward.

4) Work Ethic: How Much Sleep Deprivation Does It Take to Wake from Dogmatic Slumber?

As an honours degree, LUC is known for being extremely academically demanding. You feel consumed by your to-do list 90 percent of the time and soon you no longer distinguish between life and school, which is exactly the point of the program.

With 52 hours per week as of official study time and living in a building with 399 other nerds who love nothing more than yapping about nitrogen cycles, transaction costs, and the Vienna Conventions, you begin to feel overdosed on knowledge and caffeine, unhealthily obsessed with your personal productivity system, and sick of reading, writing, and speaking.

To give you the full picture, once you submit your third deadline of the week and can finally look forward to the six hours of sleep you’ve been craving for the past month, your roommate knocks on your door to tell you there’s a “dress as your crush” party at the college bar downstairs. You now have five minutes to put on that red dress and head down to, god knows why, sing the Piano Man till the early morning. That, too, is part of the LUC work ethic.

5) Safety Nets and Support

Because the experience is so intense, strong support systems are essential. LUC provided a safety net composed of Student Life Officers, Student Life Counsellors, Residential Assistants, Study Advisors, Academic Advisors, as well as numerous workshops and guidance on everything from mental health to sex education and substance use. This support made the immersion sustainable as safe as possible for everyone involved.

6) Finding Your Voice Outside the Classroom

Committees, clubs and societies, while not exclusive to Liberal Arts and Sciences colleges, were another important part of my bachelor’s degree that helped me discover my interests, non-academic abilities, and something my favorite stand up comedian Jimmy Carr calls' one's voice. Imagine having access to 600 people who care about roughly the same academic topics and world's problems as you, and finding that 20 of them are also into musical theatre.

You not only have fun, but you also begin to understand that there is no clear line between someone who cares deeply about poverty reduction and someone who delivers the most heart-grabbing monologues on stage while enacting SpongeBob. I have classmates for whom, shockingly, these extracurricular activities proved even more transformative than macroeconomics or climatology classes. Some became film producers, activists, or choir singers, finding remarkable ways to channel these passions into the causes they cared about most.

7) More Than Classmates

There are no words in the dictionary for me to describe how much I hate the word network. Yet, after graduating, I realized that the most valuable thing I gained at LUC was the people I befriended. This has nothing to do with calling someone to ask for a job.

Rather, as already mentioned many times, the program’s broad yet still focused emphasis on “global challenges” naturally brought together people who shared a similar set of professional values. Most of my LUC friends care deeply about making the world better rather than worse, which, I think, is a very good starting point when choosing people you want to be around.

When you care about “global challenges” (a buzzword that has become something of a universally loved meme among anyone who went through the program), it is easy to feel as though the world is constantly pushing back against you. Being part of this community means that, in moments when you feel like giving up or drifting to the dark side, you have a friend just one phone call away who is - on a smaller or larger scale - pursuing those meaningful goals we all care about. This constantly restores your motivation, hope, and a sense of belonging to a group you can be genuinely proud to be part of.

What Liberal Arts and Sciences Education Left Me With

Having never gone through a standard bachelor’s program, I cannot directly compare LUC to other models. Nevertheless, I am deeply grateful for the opportunity to pursue a Liberal Arts and Sciences education, because, for all the reasons outlined above, I believe it changed me in ways that give me confidence to work toward meaningful positive change in the areas I care about.

Beyond that, I believe it taught me to see the good in others, to understand where people are coming from, and to be a better companion to strangers, friends, and family alike. All of the experiences I’ve shared here are why I stand by the principles of Liberal Arts and Sciences education and believe they cultivate values that are essential for the functioning of any society that claims to be built on individual liberty.

Bibliography:

Husband, T. J. (2013). Cicero and the Moral Education of Youth. Georgetown University.

Nicgorski, W. J. (2013). Cicero on Education: The Humanizing Arts – Arts of Liberty. https://www.artsofliberty.org/lifelong-learners/master-teacher-thoughts/cicero-on-education-the-humanizing-arts/

Parry, R. (2003). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2024). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2024/entries/episteme-techne/

Satchanawakul, N., & Liangruenrom, N. (2025). The historical evolution of liberal arts education: A systematic scoping review with global perspectives and future recommendations. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 9, 100482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2025.100482

Sullivan, J. W. (2021). Hugh of St. Victor: Medieval Wisdom for Modern Educators. The Downside Review, 139(3), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/00125806211049724

van der Wende, M. (2007). Internationalization of Higher Education in the OECD Countries: Challenges and Opportunities for the Coming Decade. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3–4), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303543